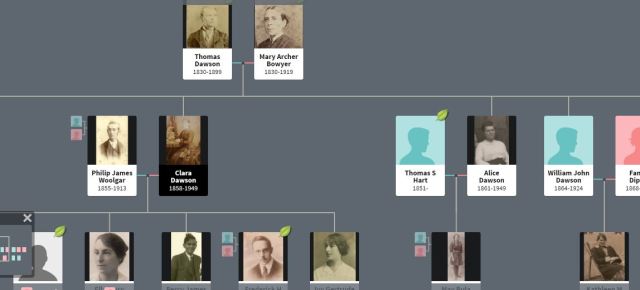

Strictly of course it is only part of her story, as there is more to be found but if I wait until it is ‘finished’ I may wait forever. So here is my attempt to preserve the memory of a lady who has no living descendants and for whom we have no photograph (yet). She is someone who could so easily be lost to history. In fact, in the past, family members did a very good job of expunging her from the oral record. As her closest living relative (jointly with my six second cousins), I felt it was up to me to investigate her life and record what I discovered, warts and all.

Fanny Amelia was the third daughter of Philip and Mary Woolgar née Cardell and was born at 6.30pm on 5th February 1848.[1] The time of birth on the certificate should indicate that this was a multiple birth but there are no other registrations for the quarter and district who could be the other sibling.[2] The address is indistinct but appears to be Cockers Haven, Finchley.[3] This almost certainly refers to a small settlement on the southern edge of Finchley Common, near the Red Lion, which was formerly named Cuckold’s Haven.[4] Finchley is now considered to be part of north London but in the mid-nineteenth century, was a small, newly-developing, settlement, distinct from the metropolis.

Fanny Amelia was baptised at St. Michael’s, Highgate on the 5th of March 1848. Her father, Philip, was described as a gardener.[5] Fanny was a surprise when I discovered her existence in the 1980s, as part of my investigations into my family history. Tales of this family were woven into my earliest memories. Why had Fanny not taken her place alongside her siblings on the first family tree I devised at the age of seven? My great-aunt, from whom I gained most of my family stories of this branch, would have been an adult when Fanny died. The families lived in close proximity, surely they would have known each other. There were photographs and recollections of Fanny’s parents, her siblings and their families but nothing of Fanny remained. Although Fanny outlived all her brother and sisters, there was no mention of her. The only acknowledgement that there may have been an additional child was the vague suggestion that Philip and Mary might have had a daughter called Sophie, so even Fanny’s name was lost to the family history. Until that is, I began my adventures in the world of archives and microfilms, of ledgers and registers, long before the advent of the internet.

The whole family appear to have escaped enumeration in the 1851 census but there was Fanny, with her parents, in 1861[7] and 1871.[8] Fanny cannot be found in 1881.[9] It has been established that she is not the Amelia Woolgar who, in 1881, was working as the cook in the Alleyn Park,[10] household of hop merchant, Stanford Mountain.[11]

On 15th November 1884, Fanny Amelia married widower, William Ellington, at St. Clement’s, Hastings, Sussex. The witnesses were Maude and H Bedwell and Thomas Covell. At the time of the marriage, William Ellington was a coachman.[12] He is inconsistent about his age and place of birth but the consensus seems to be that he was born about 1823 in Peterborough, Northamptonshire,[13] so he was considerably older than Fanny. William and his first wife, Helen, had been in service in Herne Hill for many years[14] and this is presumably how he and Fanny met.

William and Fanny Ellington’s son, George Frederick, was born in Hastings a year after they married.[15] There was another short-lived child, Richard Collings Stanley Ellington, who was born in 1891 and died the following year.[16] In 1891, the family were living in two rooms in part of 19 Cornfield Terrace, Hastings and William was working as a bath-chair man. Ten years later, the family had gained a room and were living at 100 Bohemia Road; William was still running his bath-chair business in Hastings and George was working as a compositor.[17] Although no death registration has been found for William Ellington,[18] by 1911 Fanny was a widow and can be found in the census visiting the Pierpoint family in Dulwich.[19] By this time, her son George was a boarder in the household of Harriet Blackmar, at 15 Duke Street, Eastbourne, Sussex and was still working as a compositor. [20]

On 2 May 1911, just weeks after the census was taken, Fanny was admitted to the workhouse in Constance Road, East Dulwich[21] because she was ‘temporarily disabled’ and ‘allegedly insane’. She was discharged a week letter, to Horton Asylum and described as being destitute and temporarily disabled.[22] Horton Asylum, in Epsom, Surrey, was to become noted for pyrotheraphy, an experimental treatment for the general paralysis of the insane, which was a manifestation of syphilis. This treatment involved infecting the sufferers with malaria. It was thought that the resulting high fever would destroy the spirochetes involved in syphilis. Horton was deemed suitable as it had an isolation unit, which would prevent the malaria spreading to other patients. It seems that this was pioneered in 1917, so Fanny, had she been suffering from general paralysis of the insane, would have escaped this treatment.[23]

I don’t know how long Fanny spent at Horton but on 30 December 1915, she was readmitted to the workhouse from 18 Hindmans Road. In 1911, this was the home of a younger generation of the Pierpoint family.[24] I can find no family connection with the Pierpoints, so perhaps they were just friends. Once again Fanny was regarded as ‘temporarily disabled’ and ‘allegedly insane’.[25] After just six days she was removed to Cane Hill Pauper Lunatic Asylum in Coulsdon, Surrey.[26] By this time, Horton had been requisitioned for military use.[27]

Fanny Ellington died in the asylum on 12 January 1922 from valvular disease of the heart and congestion of the lungs, both of an indefinite duration, hours after suffering a small cerebral haemorrhage. The death was registered by her son, George, who was then of 2 Grove Road, Chertsey, Surrey.[28] There was no mention of her mental state.

George Ellington married Lily Wade in 1932 in Islington district,[29] she was in her fifties so there were no children. In 1939 they were living in a tobacconist’s shop at 67 Guildford Street, Chertsey, which Lily ran; she was also a hairdresser.[30] George was still working as a compositor. They both died in 1960.[31]

The generosity of the genealogical world is outstanding. With the help of a friend, I have attempted to access the records of Cane Hill Asylum, which were allegedly in Croydon Museum. All they have is the bald statement of her admission. The quest is on for the medical records, which I understand from another helpful family historian, may be with the relevant NHS Trust. There is still the possibility of records for Horton Asylum, which are at the London Metropolitan Archives. I may have to call in another favour here. I also want to find out where she was buried; I have established that it was not at Cane Hill. The asylum was closed in 1992.[32]

So this is Fanny’s story. I do hope that more research will mean that I can add to it. Watch this space! In the absence of a picture of Fanny, I offer you her sisters, Caroline and Mary Ann [Polly], sadly, although Caroline had five daughters, she has no living descendants either. P.S. I am quite glad that I didn’t inherit the ears!

[1] The birth certificate of Fanny Amelia Woolgar 1848, from the General Register Office.

[2] General Registrar’s indexes of birth.

[3] The birth certificate of Fanny Amelia Woolgar 1848, from the General Register Office.

[4] A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 6, Friern Barnet, Finchley, Hornsey With Highgate. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1980. Via www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol6/pp38-55 accessed 4 September 2019.

[5] The baptism registers of Highgate, Middlesex, via www.ancestry.co.uk.

[6] Oral evidence from Gwendoline Catherine Braund née Smith and Ella Mary Bird née Woolgar.

[7] 1861 census for Rosendale Road, Norwood, Surrey RG9 367 folio 56.

[8] 1871 census for 1 Rosendale Road, Norwood, Surrey RG10 692 folio 59.

[9] Indexes to the 1881 census of England and Wales via www.findmypast.co.uk and www.ancestry.co.uk.

[10] Alleyn Park is in Dulwich.

[11] 1881 census for Alleyn Park, Westbrook, Camberwell, Surrey RG11 669 folios 35 & 36. General Registrar’s indexes of birth and marriage. 1871 census for Warrior Road, Lambeth, Surrey RG10 679 folio 110.

[12] The marriage certificate of Fanny Amelia Woolgar and William Ellington 1884, from the local Register Office.

[13] 1871 census for Herne Hill, Lambeth, Surrey RG10 686 folio 43.

[14] 1871 census for Herne Hill, Lambeth, Surrey RG10 686 folio 43.

[15] General Registrar’s indexes of birth; 1891 census for 19 Cornfield Terrace, Hastings, Sussex RG12 764 folio 83.

[16] General Registrar’s indexes of birth and death; 1911 census for 2 Upland Road, Dulwich, Surrey RG14 2469 folio 481.

[17] 1901 census for 100 Bohemia Road, Hastings Sussex RG13 869 folio 68.

[18] General Registrar’s indexes of death.

[19] 1911 census for 2 Upland Road, Dulwich, Surrey RG14 2469 folio 481.

[20] 1911 census for 15 Duke Street, Eastbourne, Sussex RG14 4822 folio 162.

[21] Constance Road Workhouse http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Camberwell/ accessed 4 September 2019.

[22] 1911 Admissions Register for Workhouse, Constance Road, East Dulwich, Surrey via www.ancestry.co.uk. Originals at London Metropolitan Archives CABG/185/31.

[23] Horton Asylum www.countyasylums.co.uk/horton-asylum-epsom accessed 3 September 2019. Julius Wagner-Jauregg (1857-1940): Introducing fever therapy in the treatment of neurosyphilis www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24185088 accessed 4 September 2019.

[24] 1911 census for 18 Hindmans Road, East Dulwich RG14 2466 folio 401.

[25] 1915-16 Admissions Register for Workhouse, Constance Road, East Dulwich, Surrey via www.ancestry.co.uk. Originals at London Metropolitan Archives CABG/185/40.

[26] 1915-16 Admissions Register for Workhouse, Constance Road, East Dulwich, Surrey via www.ancestry.co.uk. Originals at London Metropolitan Archives CABG/185/40.

[27] Cane Hill Asylum, Coulsdon, Surrey www.countyasylums.co.uk/cane-hill-coulsdon accessed 4 September 2019.

[28] Death certificate (pdf) of Fanny Amelia Ellington, from the General Registrar.

[29] General Registrar’s indexes of marriage.

[30] 1939 Register for 67 Guildford Road Chertsey, Surrey RG101/1876C/006/30 Letter Code: DMCC.

[31] General Registrar’s indexes of death.

[32] https://www.countyasylums.co.uk/cane-hill-coulsdon/ accessed 4 September 2019.

After an interesting and warm trip to Gibraltar, we return to the ship. The layer of pollution is evident over the sea but the views are still good. I was particularly interested in Michelle’s talk about ‘Thrulines and Theories of Relativity’. I am eager to get back to the land of the internet so that I can explore mine. It was probably just as well that it was our turn to entertain in the evening, as otherwise we would have struggled to stay awake. I have no idea why we are still so tired. ‘Coffers, Clysters’ is well-received as usual and one of our number receives a seventeenth century make-over.

After an interesting and warm trip to Gibraltar, we return to the ship. The layer of pollution is evident over the sea but the views are still good. I was particularly interested in Michelle’s talk about ‘Thrulines and Theories of Relativity’. I am eager to get back to the land of the internet so that I can explore mine. It was probably just as well that it was our turn to entertain in the evening, as otherwise we would have struggled to stay awake. I have no idea why we are still so tired. ‘Coffers, Clysters’ is well-received as usual and one of our number receives a seventeenth century make-over.

Paul Milner begins the conference with an interesting session on ‘The English Context: history, sources, repositories and processes.’ A veritable minefield for those researching from overseas, as most of the audience are; there are only five Brits at the conference. We debate why some counties are shires and some are not. Could it be the migration patterns? Why is County Durham, the only county to be described in this way? Probably because it is the only non-shire to have a county town (or indeed city) of the same name as the county, so it is a way of distinguishing between the county and the city. And so to bed. On our way past a public area an enthusiastic member of the entertainments’ team is exhorting his audience to believe they are butterflies. Numerous apparently sane adults are waving their arms, sorry wings, about. We don’t linger to find out what all this is about. The ways of cruise ships are unfathomable.

Paul Milner begins the conference with an interesting session on ‘The English Context: history, sources, repositories and processes.’ A veritable minefield for those researching from overseas, as most of the audience are; there are only five Brits at the conference. We debate why some counties are shires and some are not. Could it be the migration patterns? Why is County Durham, the only county to be described in this way? Probably because it is the only non-shire to have a county town (or indeed city) of the same name as the county, so it is a way of distinguishing between the county and the city. And so to bed. On our way past a public area an enthusiastic member of the entertainments’ team is exhorting his audience to believe they are butterflies. Numerous apparently sane adults are waving their arms, sorry wings, about. We don’t linger to find out what all this is about. The ways of cruise ships are unfathomable.

![Another Summer (A Madeleine Porter Mystery) by [Nixon, John]](https://images-eu.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51mIF8hQ5ML.jpg)

_jp.webp)

I recently discovered this beautiful photograph of a member of a family that I am researching. It isn’t actually my own ancestry but she will one day I hope be part of a novel based on incidents in her family’s life, so this could be my cover photo. She has bare feet. She lived on a cobbled street. What is it like to walk that street barefoot? I don’t know but I need to. Ok, I’ll be honest, I’m probably going to wait for better weather but I will be trying this. {Yes I

I recently discovered this beautiful photograph of a member of a family that I am researching. It isn’t actually my own ancestry but she will one day I hope be part of a novel based on incidents in her family’s life, so this could be my cover photo. She has bare feet. She lived on a cobbled street. What is it like to walk that street barefoot? I don’t know but I need to. Ok, I’ll be honest, I’m probably going to wait for better weather but I will be trying this. {Yes I