The final day of the ‘advent calendar’ focusing on some of the historical/genealogical sources that I used in the writing of Barefoot on the Cobbles.

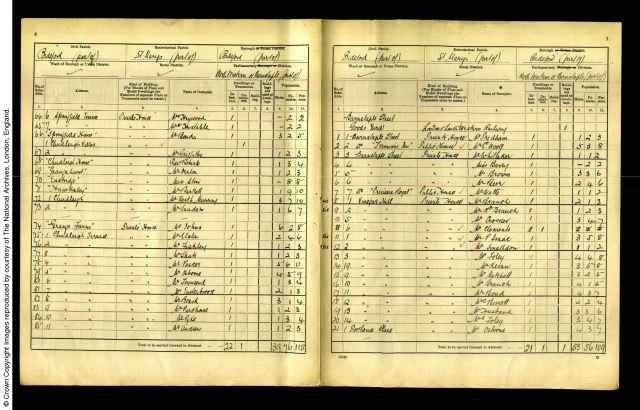

Several of the characters in the novel experience periods of mental ill-health and some of them spent time in the county asylum. I went to the Heritage Centre in Exeter where the admissions’ registers are held. The amount of information that is given varies with date but I was able to view details of my characters’ diagnoses, home life, treatment and progress whilst they were in the asylum. There were lengthy accounts of their behaviour and the symptoms that had led to their commital. Many of the personal records also give detailed physical descriptions. No photographs of Aunt Matilda survive. Everything that the reader learns of her appearance is based on what I could glean from her asylum register entry. Although I didn’t use this for the novel, an excellent website on the history of mental health is the Museum of the Mind, which focuses on Bethlem Hospital. These records are both fascinating and tragic; they are high up on my list of favourite sources.

More information about Barefoot on the Cobbles can be found here. Copies are available at various events and at all my presentations. You can order from Blue Poppy Publishing or directly from me. Kindle editions are available for those in the UK, USA, Australasia and Canada.

When tackling the horrors of the Western Front, I chose Abraham Tuke as my ‘point of view’ character. Research into his background revealed that he had been the editor of his college magazine. I decided that, like others involved in the Great War, he might relieve the stress of being in a combat zone by writing poetry. I re-read the classic World War One poets, Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sasson, Rupert Brooke, Lawrence Binyon and other well known names. I was also fortunate to have access to a collection of works by poets who are not household names and whose work is a little less polished,

When tackling the horrors of the Western Front, I chose Abraham Tuke as my ‘point of view’ character. Research into his background revealed that he had been the editor of his college magazine. I decided that, like others involved in the Great War, he might relieve the stress of being in a combat zone by writing poetry. I re-read the classic World War One poets, Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sasson, Rupert Brooke, Lawrence Binyon and other well known names. I was also fortunate to have access to a collection of works by poets who are not household names and whose work is a little less polished,  I would like to mention another local archive today:

I would like to mention another local archive today:

Previous advent posts have mentioned the importance of local archives, local history books and relevant websites, when an author is trying to recreate the geographical context for a novel that is set in the past. When my character, Polly, moved to East-the-Water, Bideford, to take up her position with the Powell family, I needed information about the area. An excellent summary of life on the eastern bank of the Torridge appears on the

Previous advent posts have mentioned the importance of local archives, local history books and relevant websites, when an author is trying to recreate the geographical context for a novel that is set in the past. When my character, Polly, moved to East-the-Water, Bideford, to take up her position with the Powell family, I needed information about the area. An excellent summary of life on the eastern bank of the Torridge appears on the  The chapter that I was most concerned about was the one set on the Western Front. It was the only location that I was unable to visit and I have no experience of being a young man, or of being in a combat zone. I read fifty or so pages of the regiment’s official

The chapter that I was most concerned about was the one set on the Western Front. It was the only location that I was unable to visit and I have no experience of being a young man, or of being in a combat zone. I read fifty or so pages of the regiment’s official  When writing of real events in the more recent past, newspapers are invaluable. I used hundreds of local and national newspaper articles during my research. The court and inquest scenes were heavily reported in many papers. In the absence of actual court records, these were vital. The huge advantage of these was that they provided me with verbatim statements spoken by the accusers, the witnesses and the accused. As someone who was more used to writing non-fiction, I was concerned about my ability to write dialogue. By the time I had used the words reported in the newspapers, I had a real feel for how many of my characters would have spoken. Newspapers were also useful when I was researching the historical background of my minor characters. For example, it was from the local newspaper that I learned that Dr Crew was about to lead a scout camp; yes, that tiny little throw-away line was based on fact!

When writing of real events in the more recent past, newspapers are invaluable. I used hundreds of local and national newspaper articles during my research. The court and inquest scenes were heavily reported in many papers. In the absence of actual court records, these were vital. The huge advantage of these was that they provided me with verbatim statements spoken by the accusers, the witnesses and the accused. As someone who was more used to writing non-fiction, I was concerned about my ability to write dialogue. By the time I had used the words reported in the newspapers, I had a real feel for how many of my characters would have spoken. Newspapers were also useful when I was researching the historical background of my minor characters. For example, it was from the local newspaper that I learned that Dr Crew was about to lead a scout camp; yes, that tiny little throw-away line was based on fact! When a novel is firmly set in a recognisable geographical location, it is important to exploit the resources of the experts. By using Clovelly as the backdrop for much of the book, I was placing my characters in an iconic village that, is well-known far beyond the immediate area. I was fortunate to be able to have access to the expertise and archive material of

When a novel is firmly set in a recognisable geographical location, it is important to exploit the resources of the experts. By using Clovelly as the backdrop for much of the book, I was placing my characters in an iconic village that, is well-known far beyond the immediate area. I was fortunate to be able to have access to the expertise and archive material of  On day three I mentioned one of the ways in which I researched the railway journeys taken by my characters when traveling between Clovelly and Torquay. Not only did I need to investigate likely routes but also the timetable that might have applied at the time. Fortunately, my library includes facsimile copies of Bradshaw’s Railway Guides. My copies are for 1922, 1923 and 1938 and I suspect that there may have been an adapted timetable during the war but I felt that these were close enough and at least this gave me an indication of how long each leg of the journey may have taken. My copies were reprinted in 1985 by Guild Publishing and there are some available on the second-hand market.

On day three I mentioned one of the ways in which I researched the railway journeys taken by my characters when traveling between Clovelly and Torquay. Not only did I need to investigate likely routes but also the timetable that might have applied at the time. Fortunately, my library includes facsimile copies of Bradshaw’s Railway Guides. My copies are for 1922, 1923 and 1938 and I suspect that there may have been an adapted timetable during the war but I felt that these were close enough and at least this gave me an indication of how long each leg of the journey may have taken. My copies were reprinted in 1985 by Guild Publishing and there are some available on the second-hand market.