We seemed to have survived Storm Agnes unscathed so headed off for Cobh, which I was pronouncing Cob but is apparently pronounced Cobe, to rhyme with robe. The railway station at Cobh aka Queenstown has been converted into a heritage centre that commemorates Irish emigration; over three million people left from Queenstown between 1815 and 1970. We were attracted by the signs to a free car park, which looked like it was going to be a fair way from the centre but turned out to loop back so as not to be, so we were glad that we resisted the lure of paid for on street parking.

There is a statue outside the centre that commemorates Annie Moore, a fifteen year old girl from Cork who was the first person to go through the immigration centre at Ellis Island, where there is also a statue of her. You can book a hour’s consultation with a genealogist at the centre for an eye watering €80. I need to put my prices up! We’d barely got through the door when Chris somehow got into conversation with someone who had been at the same school as he had and knew people he knew. I am used to this happening at home but this did seem to be quite a coincidence.

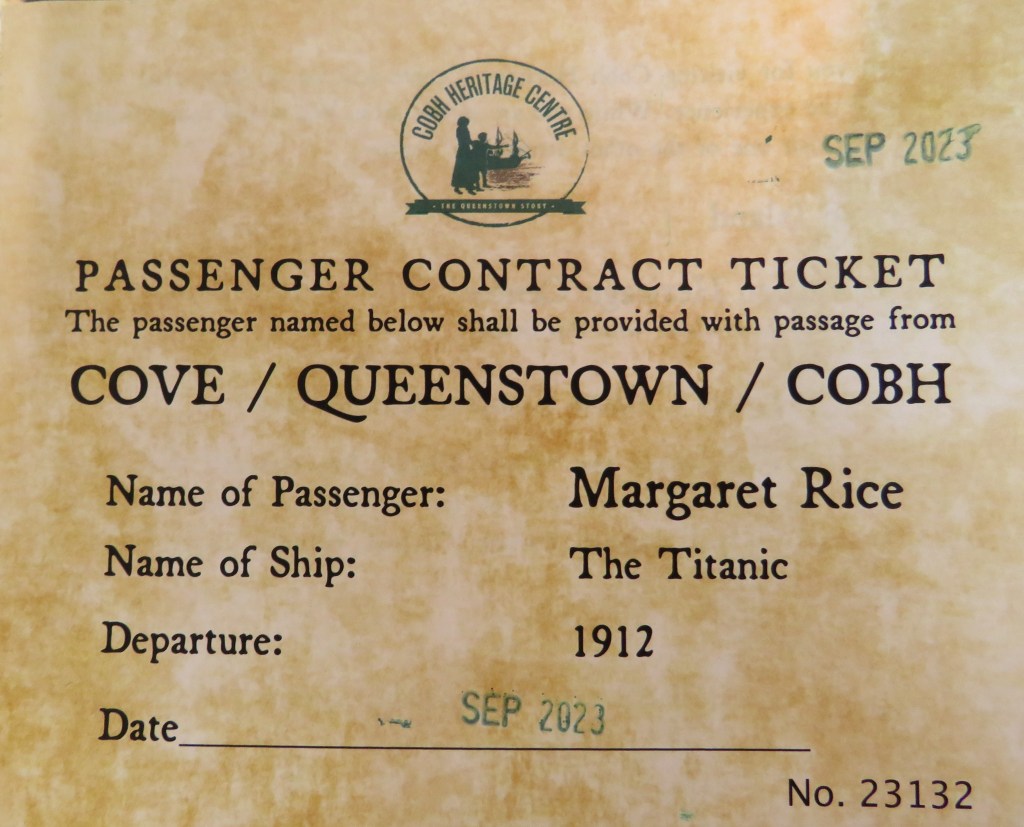

On admission to the centre we were given tickets bearing the name of a real emigrant and the actual ship on which they sailed. These emigrants left Ireland and different times in history and we were told that we would find out their fate as we went round the museum. We were both given tickets for the Titanic, so realised that this probably wasn’t going to end happily. Chris’ character was a twenty year old who eloped with a young eighteen year old to avoid being shot by her disapproving family. It is allegedly their story that inspired the film Titanic. I on the other hand was a widowed mother of five, Margaret Rice, who had been back to Ireland on a visit following the death of her husband with whom she had emigrated in 1899.

The exhibition was very well done and the personal stories were an effective touch. Several waves of emigration and emigrant ships were highlighted. Two hundred political prisoners were sentenced to transportation to Virginia in 1620. They had marched to Dublin to protest at being dispossessed of their land when Sir Arthur Chichester ‘planted’ Protestants in Wexford. From the mid-seventeenth century, Spike Island was used as a holding centre for those awaiting transportation. Many were also leaving as indentured servants. Cromwell was responsible for sending huge numbers of men, women and children to America and the West Indies, many of whose only crime was to be Irish. Kidnappers were offered substantial rewards for everyone they delivered for transportation. With around 50,000 people sent overseas in this way and sold to plantations between 1652 and 1659, in total it is estimated that Cromwell removed half a million Irish people through transportation, murder and starvation, in what was effectively an ethnic cleansing measure. In 1798, over six hundred United Irishmen were transported to Australia following an uprising. I was aware of the Roses from the Heart project to commemorate female convicts to Australia by embroidering bonnets in their name. 25,566 bonnets have been made and some were on display.

The emigrants who left from Cobh in the 1820s, many of whom went to Canada, were also part of the story. Cobh was, of course, the last port of call for the Titanic before she sailed and there was a memorial to all those from Ireland who embarked, the vast majority of whom perished, including our characters. I was pleased to see a photograph of my Margaret and her five sons. I wonder how that survived as the whole family were lost. Only Margaret’s body was recovered; she is buried in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The Lusitania, torpedoed off the Cork coast during the second world war was another disaster that was commemorated in the exhibition. 1198 of the 1959 passengers died and survivors were cared for in Queenstown and Kinsale.

Next was a bit of a drive to the supermarket of our choice. Slightly more of a drive than we’d intended because the satnav was fooled by the new road layout. We did pass some mud flats, where I glimpsed birdlife, including egrets, snipe and oyster catchers, which has been sadly lacking on this trip. On this day we clocked up more than 3000 miles since leaving home.